Fuimus, We have been.

Or, a saltire and chief Gules, on a canton Argent a lion rampant Azure armed and langued of the Second.

A lion statant Azure armed and langued Gules.

Two savages wreathed about the head and middle with laurel all Proper.

A lion statant with tail extended, Azure, armed and langued Gules.

Rosemary.

This name, now inextricably linked with the history of the Scottish nation through its association with the victor of Bannockburn, was ancient long before that momentous battle. It is believed that Adam de Brus built the castle at Brix between Cherbourg and Valognes in Normandy in the eleventh century, the ruins of which still remain. Robert de Brus followed William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, to England in 1066, and although he is thought to have died soon after, his sons acquired great possessions in Surrey and Dorset. Another Robert de Brus bacame a companion-in-arms to Prince David, afterwards David I of Scotland, and followed him when he went north to regain his kingdom in 1124. His loyalties were torn in 1138 when, during the civil war in England between Stephen and Matilda, who claimed to be the rightful heiress, David led a force into England. de Brus could not support his king, and resigned his holdings in Annandale to his second son, Robert, to join the English forces gathering to resist the Scottish invasion. At the Battle of the Standard in 1138, Scottish forces were defeated and de Brus took prisoner his own son, now Lord of the lands of Annandale. He was ultimately returned to Scotland, and to demonstrate his determination to establish his branch of the family in Scotland, he abandoned his father's arms of a red lion on a silver field and assumed the now familiar red saltire. The arms borne by the present chief allude to both elements.

William the Lion confirmed to the son the grant of the lands of Annandale made to his father by David I. Robert, fourth Lord of Annandale, laid the foundation of the royal house of Bruce when he married Isobel, niece of William the Lion. She also brought extensive estates, both in Scotland and England. Princess Isobel's son, another Robert, known as 'the competitor', was at the time named heir to the Scottish crown. However, his claim was challenged by the birth of a son to the daughter of his wife's elder sister, who was married to John Balliol. On the death of Alexander III in 1286 there commenced the contest for the succession to the Crown between Bruce and Balliol. The death of the child heir to the throne,, Margaret, the maid of Norway, in 1290, opened the competition for the succession once more, and to avoid a civil war, the rival claimants asked Edward I of England to act as arbiter. In 1292 Edward found in favour of John Balliol. But Edward was not content to advise on the selection of the new monarch, and asserted a right of overlordship in Scottish affairs. Balliol attempted armed resistance but was decisively defeated at the Battle of Dunbar in 1296. His defeat left the leadership of Scotland in the hands either of the powerful Comyn family or the Bruces. Robert the Bruce met John Comyn in February 1306 in the Church of the Minorite Friars at Dumfries. Bruce stabbed his rival in the heart, and his companions dispatched the rest of the Comyn party. Within weeks Robert was crowned King and began a long, hard campaign to make his title a reality, culminating in the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. He set about rebuilding the shattered nation and it is a considerable tribute to his leadership and abilities that he substantially achieved his objectives. In 1370 the first Stewart monarch succeeded to the throne by right of descent from Marjory, Bruce's daughter.

Thomas Bruce, who later claimed close kinship with the royal house, organised with Robert the Steward (later Robert II) a rising in Kyle against the English in 1334. He received in recompense part of the Crown lands of Clackmannan.

Sir Edward Bruce was made commendator of Kinloss Abbey and appointed judge in 1597. In 1601 he was appointed a Lord of Parliament with the title of "Lord Kinloss". He accompanied JamesVI to claim his english throne in 1603 and was subsequently appointed to English judicial office as Master of the Rolls. In May 1608 he was granted a barony as Lord Bruce of Kinloss. His son, Thomas, was created first earl of Elgin in 1633. The fourth Earl died without a male heir and the title passed to a descendant of Sir George Bruce of Carnock, this branch of the family had already been created Earls of Kincardine in 1647, and thus two titles were united.

The seventh Earl of Elgin was the famous diplomat who spent much of his fortune ressuing the marbles of the Parthenon which were at that time falling into utter ruin. His son was an eminent diplomat and Governor General of Canada. He led two important missions to the Emperor of China. He was Viceroy of India, a post also held by the ninth Earl of Elgin from 1894-1899.

The present Chief- the eleventh Earl of Elgin and fifteenth of Kincardine- is prominent in Scottish public affairs and is convener of the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs.

Legacy of the Bruce

Among the many illustrious members of the Family of Bruce, none is more famous than the warrior king, Robert I, known simply as "The Bruce." Subsequent to taking the throne and after many years of struggle against, not only the English, but also some of his own countrymen, The Bruce led Scotland from under the yoke of its southern brethren at the Battle of Bannockburn and cementing the independent sovereignty of Scotland. After seizing the throne in 1306, The Bruce met with a number of defeats at the hand of Edward I. He barely escaped to an island off the west coast of Scotland where he bid his time, waiting for the right opportunity. It was while in hiding that the famous story of his studying the efforts of a spider in a cave occurred. While watching the spider continue to try to swing from one wall to the next to build its web, The Bruce learned a valuable lesson about perseverance. It is said that the phrase, If at first you dont succeed; try, try again was coined from this experience.

Further, as a spider modifies its web to fit into the area in which it finds itself, Robert also learned to adapt his fighting style to match his assets and circumstances. Robert knew that he had little chance of defeating the English in a structured, pitched battle. He lacked the proper resources. However, if he practiced what we now know as guerrilla tactics, he could make surgical strikes of growing importance. This he did through 1313 and, in doing so, had conquered virtually every important fortification in Scotland, save one - Stirling Castle.

Robert's brother, Edward, had negotiated a deal whereby, the castle would be surrendered to the Scots if it was not reinforced within a year. Unfortunately, this deal gave the English what they had been unable to compel - require Robert to engage in a formal battle. Further, it allowed the English to prepare a large invasion force to hopefully deal the insurgent Scots a crushing blow. Luckily, times and circumstances were not completely stacked against The Bruce. His former friend and, later, bitter adversary, Edward I, had died, leaving an inexperienced son in his stead. Also, since Robert was under an excommunication from the Pope, Scotland proved to be a safe haven for a strong, wealthy, and disciplined military order also at odds with Rome - the Knights Templar. These two factors, along with the time to prepare before Edward II's advance, proved to be critical in Scotland's War for Independence.

Although his personal courage was not in question, Edward II was not the general his father was. Not only did he fail to realize how to effectively use his forces, especially his archers and cavalry, but he never clearly established a chain of command amongst his nobles. As a result, the nobles spent almost as much time and energy battling for position with their king as they did in preparation for battling The Bruce. Thus, Edward II was unable to capitalize on his numerous advantages over the Scots.

One of the most controversial theories concerning Bannockburn was the battle that the Knights Templar may have played in this drama. The Knights Templar were originally established as a result of the Crusades. In 1118, nine Crusaders founded The Order of Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon. The order was established to keep the highways safe for pilgrims in the Holy Land. Although the individual knights took an oath of chastity and poverty, the Order became extremely wealthy and powerful.

Additionally, the Knights earned a reputation as ferocious warriors, obligated to fight to the death and never to retreat. In fact, their distinctive badge, the splayed red cross, was worn on the fronts of their surcoats only. They wanted their foes to always see the cross, so they would never turn their backs in retreat. Further, by the thirteenth century, the Templars were believed to possess magical powers, a myth that generated great fear and skepticism among the general populace. The Templars then became the first standing professional army in Christendom - another factor creating great fear among others. Nonetheless, Pope Innocent II in 1139 issued a Bill that the Templars were responsible only to the pope; not subject to any other secular or church authority. Thus, so long as the Knights were needed in the Holy Land, there was little to fear on the home front.

This changed. As a result of the fall of Jerusalem in 1291, the Templars moved their headquarters to Cyprus and obliged to find another reason for their existence. By 1306, it was rumored that they intended to establish an independent kingdom in southern France. This was not a welcome development for Philippe IV of France and there was a major power play between the Knights Templar and Philippe. A propaganda campaign depicting the Knights as heretics was begun in earnest and Philippe, playing upon the fear and jealousy of the Templars as well as the overall malaise at the Christians being expelled from Jerusalem (which the Templars were sworn to defend), persuaded Pope Clement V to excommunicate all Templars for heresy. The Order was officially dissolved in 1312 and all secular authorities were empowered to arrest the Templars.

In March 1314, the last Grand Master of the Order of Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple, Jacques DeMolay, was roasted to death over a slow fire on the Ile de Seine. Obviously, the remaining knights needed sanctuary. Scotland fit the bill perfectly. In fact, the Templars already owned considerable properties in Scotland and, with Edward II's outstanding order to arrest all Templars, relocating to Scotland was a logical choice. That the Templars should safely remain in Scotland was further aided by two other factors. First, in 1309, Edward II ordered his appointed Guardian of Scotland, Sir John de Segrave, to arrest all Templars in Scotland and report them to the Inquisitor's Deputy. This deputy was Bishop William Lamberton of St. Andrew's who, while paying lip service to the English king, was totally loyal to The Bruce.

Second, Robert himself had been excommunicated by the pope as a result of an incident with Red Comyn at Greyfriar's Abbey in 1306. Although The Bruce desperately wanted to reconcile himself with Rome, he wanted to be King of an independent people more. Further, as a result of his strained relationship with the pope and the loyalty of the principal clergy in Scotland, Papal Bulls were never proclaimed in Scotland. Technically, since they had not been so proclaimed, the Templars had not been legally dissolved in Scotland. Thus, The Bruce had nothing more to lose by providing the Templars a safe haven in Scotland.

Archie McKerracher in his article, Who Won at Bannockburn? The Highlander, July/August, 1994, surmises the following scenario. In December 1309, Bishop Lamberton interrogated the two principal Templars in Scotland at Holyrood Abbey. However, instead of questioning them on charges of heresy, it is likely that he made them an offer they could not refuse, "Supply us with arms, money and expertise and we will give the Templars sanctuary in the only land where the Pope's writ does not run." They apparently accepted this arrangement for, shortly thereafter, arms began to arrive in great quantities and the Templars were the only ones with storehouses of weapons and the means to transport them to Scotland.

The matter of arms is another compelling indication that the Templars were involved with the Battle of Bannockburn. At the time in question, Scotland was a poor nation, especially having to bear the economical brunt of being at war with England for more than twenty years. Normally, each soldier had to provide his own armor and weapons. The typical Scot probably did not have much to aid him in this area. Yet, it was clear that the Scottish soldiers at Bannockburn were relatively well equipped. Given the fact that the Templars were extremely wealthy, had a great cache of arms, and the means to transport them, it is not a great stretch of imagination to suppose that they provided the necessary assistance. In the first weeks of summer in 1314, we found Robert the Bruce in earnest preparation for the imminent battle with Edward II, a battle for the very existence of an independent Scotland.

The previous year, Robert's brother, Edward, negotiated an agreement with the English who held the strategic center of Scotland, Stirling Castle. That agreement dictated a surrender of the castle to the Scots unless the English garrison was relieved by the next feast of St. John the Baptist, June 24, 1314. The strategic and political value of Stirling Castle made its relief by Edward II and the English host inevitable. The invading forces from the south have been estimated at approximately 100,000, including massive amounts of archers and light and heavy cavalry. The Scots had somewhere in the 30,000 range - mostly infantry with some light cavalry. These appeared to be seemingly insurmountable odds. Nonetheless, the Bruce had a number of advantages.

First, he could choose the battlefield, as well as his position therein. Second, he was fighting Edward II, not Edward I. Third, and sometimes underrated, the Scots were fighting at home for their homes. It has been said that the vast majority of the Scots fighting were landowners since it was felt that only those with a stake in the land could be trusted to fight for it.

Thus, we find the Bruce in June, 1314, preparing the battlefield on the northern banks of a substantial side stream of the River Forth, the Bannockburn. The English, coming from Edinburgh, were marching from the south and the only way to reach Stirling before the appointed date was along an old Roman road. Although this was the only route for such a large contingent, it was less than an ideal pass.

Along this route, the Bruce had numerous pits dug, about 3 feet deep and a foot wide with a stake in the middle and covered loosely with sod and/or branches. Additionally, he had a number of calthrops (iron triangles made so that one point was always pointing up) strewn about to lame oncoming horses. Although this could not stop an advance, it would greatly slow it down, leaving it vulnerable to counterattack and create confusion within an attack. To the east lay a carse, or bog.

This was large, low and open; all of which became very important. Consisting primarily of infantry, the Scots utilized a technique of placing a great number of men (upwards of 3000) very close together in the shape of a box. Each man carried a 14 foot long spear or pike. This formation was called a schilltron. It was extremely effective against cavalry where the pikes were used to disable the oncoming horses and unseat their riders. Once on the ground, the rider was quickly engulfed and dispatched by the infantry. The Scots infantry was well trained and was able to move as one more quickly than one could realize.

The Scots army was located on higher ground in a wooded area called the New Park. Initially, the Bruce set his forces in defensive positions waiting for the English to make their way through the pits and traps up the road toward Stirling. On June 23, Edward II sent two advance parties of cavalry to investigate the area around the New Park. The first party traveling up the Roman road was led by Sir Humphrey de Bohun, nephew of the Earl of Hereford. As luck would have it, he came across the Bruce himself, who was also inspecting his troops and the field. The Bruce had only a small contingent attending him. Recognizing the King of Scots and such a prime opportunity, de Bohun set his lance and began a charge. The Bruce, on a smaller horse and wearing only mail for armor, was ill equipped to meet de Bohun in like fashion, took his battle axe and rode cautiously to meet de Bohun. Waiting until the last possible moment, he spurred his horse to the side, dodging the lance, and as de Bohun passed, he struck him with such force as to not only kill him instantly, but also to break his axe.

(This is probably the only supreme moment of personal combat of any sovereign of the countries of the British Isles.) The accompanying Scots ran off the remaining English, with the Bruce commenting on how he was sorry to have broken a perfectly good axe. The second English advance party was led by Sir Robert Clifford and Sir Henry de Beaumont. This party went a little further to the east from the first, along the carse road. As it approached, a schilltron under Thomas Randolph began to form from infantry pouring from the trees. Sir Thomas Gray, a Yorkshire knight, argued with de Beaumont for an immediate attack. De Beaumont, confident that they could defeat this group of Scots, decided to wait until more of the Scots joined the field so that their would be more Scots casualties when the battle was joined. Gray attacked anyway and was immediately killed. Other knights also attacked, but not in any type of organized attack and, accordingly, were killed in turn. The English broke, most of which returned to the main English host. Edward II, seeing that a frontal assault on the Scots would be difficult at best, decided to attempt to flank the Scots to the east, following Clifford's route.

It was one thing for a small party of cavalry to skirt the New Park and avoid the carse; it was another to move an entire army into this open, inviting area. Still, Edward II moved his army across the Bannockburn and over to the east into the carse to begin their advance to Stirling. By the time all of the army crossed and shifted to the east, it was late in the day and time to set up camp. The intent was to begin the final assault in the morning. Edward could not have picked a worse place to camp. His men and horses were blocked to the rear and to their right by water and the land they occupied became a muddy bog.

They were also cramped, so not only were they hampered by being stuck in the mud, there was no room to maneuver. The Bruce quickly assessed the situation and quietly moved his troops from their defensive positions into place to meet the English before they could extricate themselves. The Bruce divided his infantry into four divisions. The center was commanded by Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray.

To his left, the division was nominally led by the Steward, young James Stewart, but was effectively headed by James Douglas and to his right, by Edward Bruce. The Bruce himself led a fourth division held in reserve. The cavalry, captained by Sir Robert Keith, the Marischal, was positioned to the far left to protect the Scots from an advance from Stirling Castle, as well as protect the exposed left flank.

In the predawn hours of June 24, the Scots received blessings from the clergy accompanying them. They, then, quietly moved into position to attack the English before the English could realize their predicament. Still, before the Scots could actually meet the invaders, they had an opportunity to hastily draw up into two lines, the front line was made up of cavalry of approximately nine squadrons of 250 riders each. Nonetheless, the English were penned into a tight, muddy area severely limiting the ability of the cavalry to mount an organized, effective charge.

To the right, and opposite Sir Edward Bruce, the Earl of Gloucester impetuously attacked, virtually alone. There are varying stories as to why Gloucester acted in such an undisciplined manner, but it pointed out the lack of a firm chain of command and battle plan by Edward II. Nonetheless, Gloucester attacked and was immediately killed. Edward Bruce's forces pressed the situation and advanced against the English. Upon seeing this, Randolph led the center and shortly thereafter, Douglas moved forward on the left so that the entire front was at issue. The Bruce kept his forces back a bit though they began seeing some action along the left flank. Still, the Bruce was most concerned with the English archers which to this point had not been effectively deployed. The archers would be utilized much like artillery and the Scots had virtually no defense against them. Edward I routinely used the archers to send wave upon wave of shafts into the Scots infantry to weaken them before committing his cavalry to finish the job. Edward II did not learn this lesson.

Finally, the archers attempted to move to the higher ground on the left. Once they were there, they began to unleash a deadly rain upon the Scots. The Bruce then quickly dispatched the cavalry under Keith. The archers had no defense and were quickly dispersed. Meanwhile the carnage below continued. Pressing the advantage of the field and the inability of the English to mount an effective counterattack, the Scots were persevering, but the Bruce could see that the time would soon come where they would tire and the superior numbers of English may begin to turn the tide. It was at this time that he unleashed his surprise weapon - his reserves from a place in the rear called Gillies Hill. There are at least three versions of who made up these reserves.

The traditional story was that the reserves were a mass of camp followers and untrained, ill-equipped, common folk. Although there were supposed to be a quite large number of them, it is highly unlikely that the English, who were experienced soldiers, would be afraid of such as these, nor believe them to be a substantial new army. A second account, says that the reserves were an unknown number of highlanders. The highlanders were respected as fierce warriors and feared as barbarians by the English. Still, if confronted with an unorganized horde, the English may not feel sufficiently threatened to break and run. The third story is really a modification of the second.

This account has the highlanders being visibly led by members of the Knights Templar. As we discussed above, the appearance of the Templars was sufficient to put the fear of God into almost any man. Seeing them at the head of a horde of barbarian-like highlanders would be enough of a demoralizing event as to cause the English to abandon their fight a bid a hasty retreat. Thus, the Bruce committed his reserves. The English, feeling that all was lost, broke and ran. Many were killed in the retreat. Many were taken prisoner and ransomed. Edward II escaped and made his way back to England, but never made another real attempt toward Scotland in his lifetime. Scotland was free. The spirit of that freedom was eloquently stated a few years later in a letter to the pope called " The Declaration of Arbroath".

The most poignant passage is at the end:

... so long as there remain 100 of us alive, we will never give consent to subject ourselves to the dominion of the English. For it is not glory, it is not riches, neither is it honors, but it is liberty alone that we fight and contend for, which no honest man will lose but with his life.

- There are few references to draw upon to get an accurate picture of what happened at Bannockburn. The two most traditionally authoritative are: The Lanercost Chronicles, written by Augustinian friars representing the English point of view, and The Brus, an epic poem by John Barbour telling the story from the Scots perspective. Neither of these resources mention the Knights Templar. However, since it would not have been politically astute to mention, much less glorify, an outlawed, and supposedly non-existent group, such an omission may not be hard to understand. Still, the presence of the Knight Templar is only a theory, and is one that is not widely supported, but certainly is plausible.

Name Variations: Bruce, Brus, Carlyle, Carruthers, Crosbie, Randolph, Stenhouse.

References:

One or more of the following publications has been referenced for this article.

The General Armory; Sir Bernard Burke - 1842.

A Handbook of Mottoes; C.N. Elvin - 1860.

Scottish Clans and Tartans; Neil Grant - 2000.

Scottish Clan and Family Encyclopedia; George Way of Plean and Romilly Squire - 1994.

Scottish Clans and Tartans; Ian Grimble - 1973.

World Tartans; Iain Zaczek - 2001.

Clans and Families of Scotland; Alexander Fulton - 1991.

|

|

The beautiful heraldry artwork for this family is available to purchase on select products from the Celtic Radio Store. We look forward to filling your order!

|

|

|

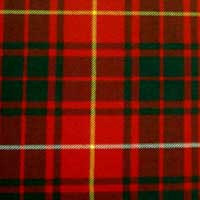

Ancient |